NUCLEAR APPROACH TO WEIGHT VESTS

Discover how weighted walking significantly boosts calorie burn using the military-backed Pandolf Equation. Learn how weight vests, incline, and terrain amplify your fitness results far beyond standard estimates.

Do you want to burn even more calories?

In my last piece we dived into the question: does the weight vest burn more calories? I hate the fact that I have to write something that is so unequivocally logically obvious…yes it does. To think otherwise would be frankly pretty stupid.

The argument against vests was that it doesn’t burn that much. When the rubber meets the pavement we are talking 1 calorie a minute, sometimes less, sometimes more. I’m not going to get into the long term math here, but what seems like a small number, is actually a big number when we can agree to the fact that longer term commitments can lead to better results, but require consistency and the ability to put in the work.

If you are that person you are going to like the rest of this article; light vest work was just the beginning.

TLDR; Light vest work roughly about 5-10% body weight burns roughly 0.5-1 calorie per minute for most movement activities.

Now to the real talk: Pandolf equation.

The Pandolf Equation is a military-developed formula used to estimate energy expenditure during walking while carrying external load. It is one of the most widely cited models for predicting how much harder walking gets when you add weight and accounts for things like grade and different terrains.

E=1.5×W+2.0×(W+L)×(2WL)2+η×(W+L)×V2

This tends to look like some “Good Will Hunting” stuff but effectively it states that you burn more calories walking with more weight, as the grade increases, and as the terrain becomes more difficult (sand, snow, mud, etc.).

I never fully understood this equation until I thought back to a distant memory of a hike I did in Canmore in my early twenties. It is a vivid memory, not only because of the hike itself, but because of what I ate after and the 0 effect it had on my weight.

My wife and I scaled Lady Macdonald on one beautiful summer day. When word of mouth was king, this trail in the heart of the Canmore was said to be for beginners. I don’t know who the fuck thought that but it was essentially a 45% grade for the first hour and we bonked out and half way up. Went too hard at the beginning; Inexperience at its best. We slowly made our way to what we thought was the top, sat down and ate our packed lunch, and realized we still had a small scramble to the top to sit on a vantage point that was supposed to be worth it all. We said fuck that because we didn’t have enough food and we were extremely hungry already, thinking this was an easy hike. It was 2 hours to the near summit, with an insane grade, switch backs, and climbing up massive stones.

We headed down, which for anyone used to hiking, the way down isn’t necessarily easier with the eccentric load the whole way down..but it is faster. At completion I wouldn’t say we were completely dead, because we took it pretty easy after the bonking. It was hours of walking with packs filled with food and water, and tough terrain. I don’t think I’ve been hungry in my life outside of my extreme water cut for Powerlifting Nationals where I lost 30lbs in a week and needed to reconstitute weight before stepping on the platform…that is saying a lot trust me.

The reason why this story is important is because of what we did after. The legendary ‘La Poutine’ (now closed) was the first place we stopped because we wanted calories, we wanted salt, and we wanted it now. For those of you who don’t know of the legend, ‘La Pountine’ hosts every type of poutine you could think of with the house special being a Montreal-Style poutine mixed with cheese curds, fries, gravy, and smoked meats. All the calories.

Not only did I not gain a lb the whole trip, I felt absolutely amazing following the act of gluttony. I’ll never forget it. I outworked a bad diet!

This was before the age of all trails and constant monitoring of fitness wearable, so I don’t have the exact numbers, so this isn’t science at its best but it highlights a key point. I burnt a lot of calories and I ate a lot of calories.

Now what’s going on here? And more specifically how do we take this concept of external weight and put it on steroids for people that want to take science and math and talk about this tools in a way that fucks shit up and doesn’t deter people from doing more?

Well I’m glad you asked.

Let’s define terms here. Previously we used MET scores to estimate simple calories for walking under simple standards. The MET score system is great but falls apart when we try to introduce multipliers and super contextual variables. It’s more or less a guide to rank easy activities to harder activities and assign them a number for calorie expenditure estimations.

What’s the Difference Between MET Estimates and the Pandolf Equation?

MET Estimates (What Most People Use):

METs (Metabolic Equivalent of Task) are population averages of calorie burn, gathered from indirect calorimetry studies.

They tell you how much energy the average person burns at a given speed or activity, like walking or running—but they don’t automatically adjust for load, incline, or terrain.

METs are easy to use because they’re simple:

Calories/min=200(MET×3.5×bodyweight in kg)

Pandolf Equation (Load-Specific, Physics-Based Model):

The Pandolf equation was designed by the military to predict the actual energy cost of walking with external load (like vests, packs, or rucks).

It considers:

Bodyweight + Load

Speed squared (

V2)Terrain difficulty (flat, sand, snow, hills)

Incline/Grade

TL;DR:

METs = population averages for calorie burn.

Pandolf = physics-based formula for calorie burn with load, hills, or rough terrain.

Use METs for general fitness estimates.

Use Pandolf when you’re carrying weight or walking on incline.

Now let’s do some math.

Previously we looked at what was the extra calorie math for 10% extra load so I want to revisit that with the added use of Pandolf Equation accounting for grade, terrain, and both of them combined as multipliers. For sake of similar comparisons I used 3.5 mph walking as the constant here, so numbers will vary depending how slow or fast you choose to walk…but it’s walking, not running.

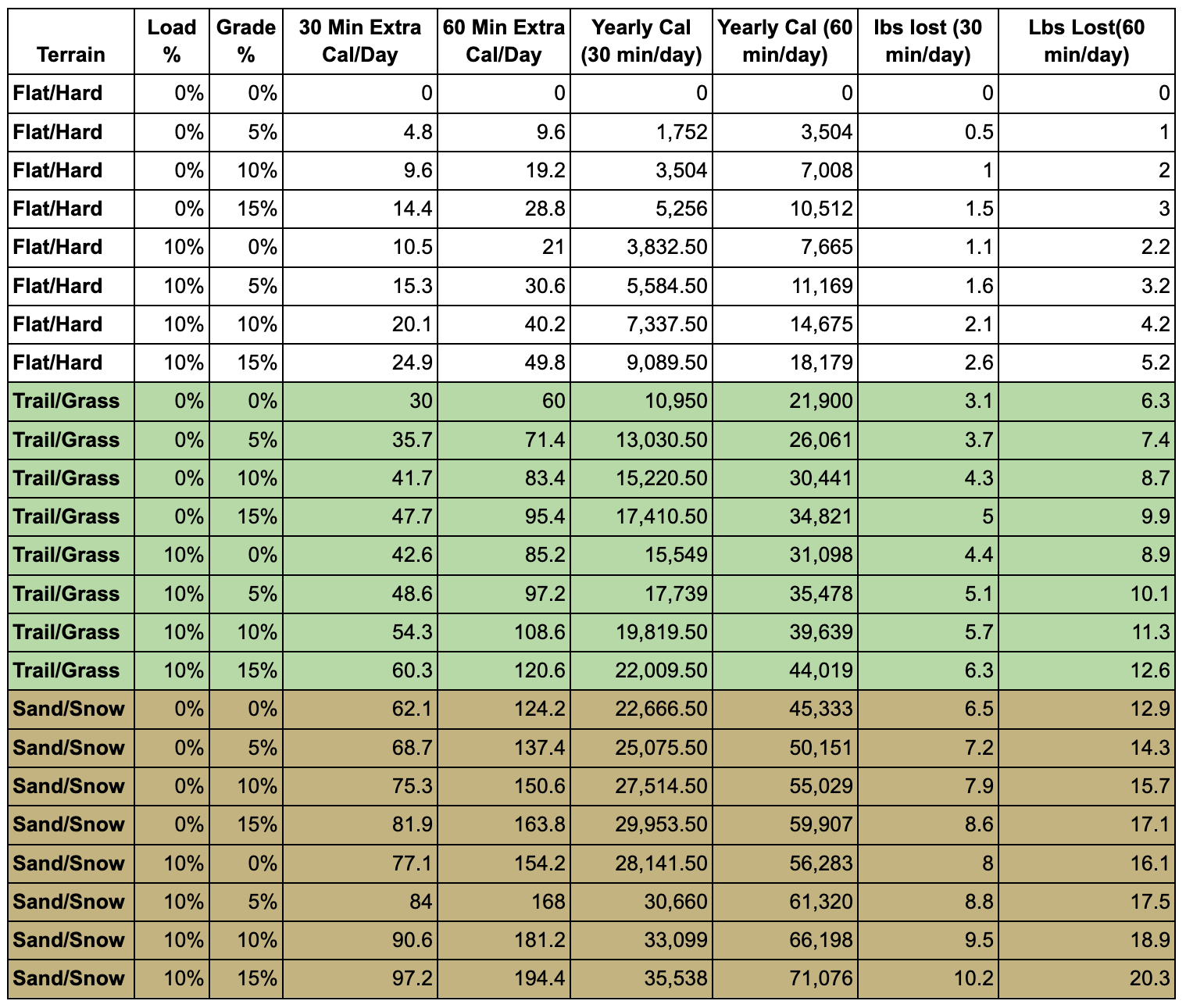

The following table:

The cool thing about this is previously we looked at small changes of 1 calorie per minute for running, but this was for running and it was much more reduced when we looked at walking at about 0.68 calories per minute extra. The Pandolf equation usually gives a lower calorie estimate than standard MET-based calculations because it’s designed to measure mechanical work and external load carriage, not total metabolic cost including inefficiencies. Generally speaking it’s about 25-30% difference, with the Pandolf consistently lower. I’m okay with this because lower means we have the chance for it to actually be much higher, but we have to work with what we’ve got, which is a common strategy for most evidence based people…for good or bad we die on that hill…well in this instance we are going to use that to use a lower estimation so that no one can claim that I’m trying to oversell the hype. To repeat. The Pandolf Equation is much lower in calorie expenditure estimations. Let’s continue.

What does this look like in a yearly context for both 30 minutes a day, 60 minutes a day, with both calories expended and weight loss in lbs.

The following table:

This is pretty interesting. We are talking double and triple the numbers from our previous experiment. Seems like weighted wear and other multipliers starts to make walking look pretty damn good.

Now let’s look at the nuclear plan. You aren’t average and you want to start to stick it to the people who think external weight and walking burns a measly 0.5-1 calorie a minute. This is where the real fun begins.

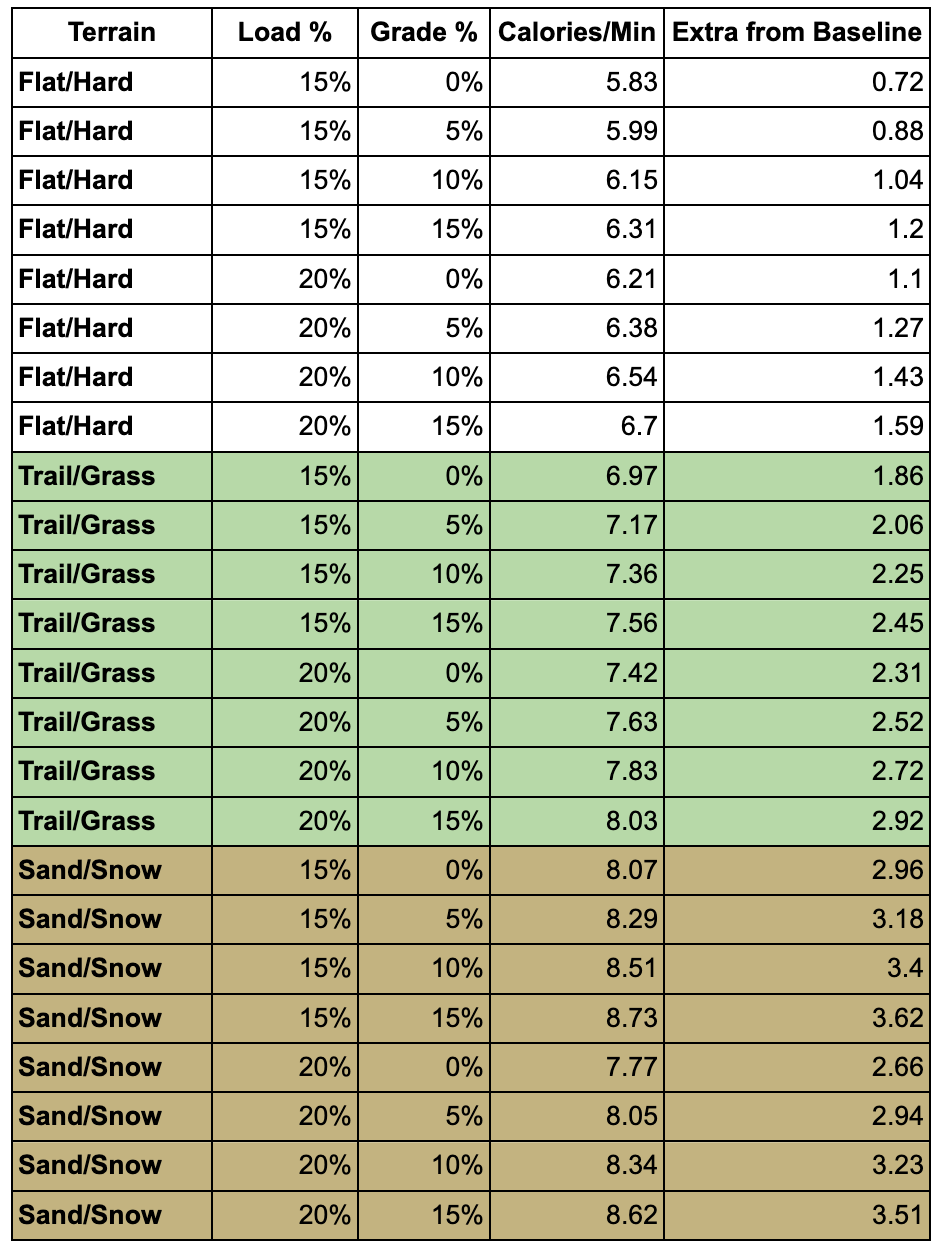

We are going to look at these same charts but with the 15% and 20% extra load respectively.

The following table:

Now we are cooking with oil. Remember that The Pandolf Equation is arguably lower, we are achieving numbers on par with running with a weight vest at the lower end with adding a vest plus increasing grade, and as much as 60% percent higher with 20% added load. That is only on flat/hard surfaces.

I am almost hesitant to start to push trail/grass and sand/snow just because of the nature of the fact not everyone can control for that, but if we dive into those categories we are talking SUBSTANTIALLY higher upwards of 3.51 calories a minute. That would be overselling it based on the fact we aren’t going to find that terrain in most people's situations. That being said, it’s there for you to see.

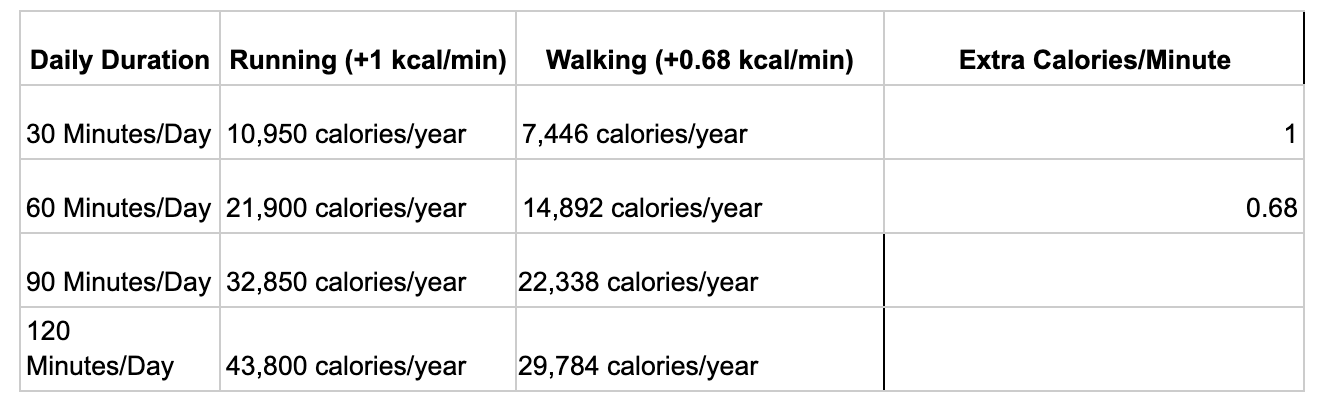

Let’s finally convert this chart into calories.

The following table:

The Bottom Line: Your Secret Weapon for Calorie Burn

I'll leave this here, but we aren't talking in small numbers anymore. I must also remind you that these figures are above and beyond what we would expend doing the same amount of time walking with 0% added weight. This doesn’t even account for the simple fact that increasing our time fighting gravity while walking is a weight loss tool in its own right.

So, if you're looking for a low-impact, highly effective way to significantly boost your calorie expenditure, the answer is clear:

Weighted walking is your secret weapon. It's not just about tiny increments; it's about harnessing the power of physics to amplify your efforts, leading to genuinely impactful results over time. Don't let anyone tell you that a weight vest only burns a "measly" 0.5-1 calorie a minute. The science, and my own experience, tell a very different, far more exciting story. Go put in the work, and watch the numbers add up.

DO WEIGHT VESTS BURN MORE CALORIES?

Do weight vests actually help you burn more calories? Here’s what the science says, plus how small calorie increases add up for fat loss over time.

Does a Weight Vest Burn More Calories?

The weight vest: a topic that frequently surfaces, often presented either as the ultimate fitness solution or as a complete scam.

If you grew up in the late 90s/early 2000s, you'll recognize the common trope that weighted clothing is the perfect way to conceal your true strength. Then, when the chips are down, you ditch the gear and unleash newfound power and speed to defeat your enemies. This, of course, is what Goku did time and again, and he is arguably the strongest warrior in the world.

While this might seem like a joke, is there any real truth to this seemingly infallible logic? The answer is nuanced, and I believe it warrants a full series. For now, I’m going to address one of the most common questions about weight vests: Do they burn more calories?

Other topics to explore further down the line include:

Does it increase bone density?

Does it help lose fat? Maintain muscle?

Does it help build muscle?

While all these questions are hot topics in their own right, I’ll save them for a later date. This is mostly because the current topic, calories, is something most people readily believe. Yet, when data is presented by those against it, they often undersell the value of small metrics to dissuade people, all in the name of fighting the charlatans who promise big results. Let’s take a closer look.

Full disclosure: I'm with Goku. Goku always has been, and always will be, the greatest fighter the universe has ever seen. If it’s good enough for him, it’s good enough for me.

The main referenced study, in terms of direct calorimetry and measurement, is “Predictors of Fat Oxidation and Caloric Expenditure With and Without Weighted Vest Running.” This is a relatively recent study (2019) that sought to investigate how adding external load (weighted vests) affects:

Fat oxidation rates

Total caloric expenditure

Exercise tolerance and fatigue

Basically, the researchers aimed to answer the question: if we put people on a graded treadmill running, does it burn more calories with a vest versus without a vest? The study involved three different tests: one with no vest, one with a vest at 5% body weight, and one with a vest at 10% body weight. Simple enough.

Here's what it found:

Increased Caloric Burn with Load: A 10% bodyweight vest increased caloric expenditure by approximately 1 extra calorie per minute. This aligns with about a 7–10% increase in energy cost compared to running unloaded.

Fat Oxidation Shift: Fat oxidation increased at lower intensities with the added load but decreased faster at higher intensities due to quicker fatigue and a crossover to carbohydrate utilization.

Time to Exhaustion Decreased: Loaded runners fatigued about 6% sooner at the same relative intensities. This suggests the added load increases neuromuscular strain, not just metabolic cost.

Body Composition Matters: Body fat percentage was inversely related to fat oxidation rates. Leaner runners oxidized more fat, even under load.

No Sex Differences: Men and women responded similarly in terms of calorie burn and fat oxidation patterns.

The key findings weren’t particularly mind-blowing, and how you interpret the results really depends on your perspective regarding fitness and nutrition processes. If you view it as a small number, you might be the short-term individual who sees absolutely no benefit. If you see massive potential, you are someone who is in it for the long haul and can appreciate delayed gratification… and can do simple math. You could say the same thing for the people presenting these findings on social media, but that’s a topic for another day. And truthfully, in a world where people are desperately seeking attention, I understand the appeal of hot takes. But I genuinely dislike hot takes made at the expense of simple math; and I'm not even a "math guy."

So, does a weight vest burn more calories? Yes. Yes, it does.

How many calories does it burn? Around 1 calorie per minute, give or take, depending on varying percentages of body weight and the weight vests used… but roughly 1.

Let me present two scenarios for interpreting this data.

The Short-Term Person or Influencer Looking to Go Viral (hating on vests): "1 calorie?! That’s it. A whole calorie a minute? Effectively useless. Just stop putting creamer in your coffee. Problem solved."

The Longer-Term Person Who Can Do Math and Believes Goku Got It Right: "1 calorie a minute seems small, but the study said there's a 7-10% increase in energy cost. That seems legitimate, right? Let’s just do some quick math."

Let’s use a modest number. 60 minutes a day. One year…

Well, would you look at that: 6.26 lbs a year. That’s not too shabby for something you simply add to an activity you’re already doing.

Now, I'm being a bit illustrative here, and that's to prove a point: when we, as professionals, present this information, we hold significant influence over how people make their fitness decisions. Our words carry weight, and dissuading someone from a legitimate tool simply because of a "small" number seems a bit aggressive.

In the spirit of trying not to be that person on the opposite end of the spectrum, I’m going to break this down in a more realistic way. I believe most people aren't going to run 60 minutes a day with a vest. BUT, I think there is significant merit to using them for a base built around walking.

Consider 60 minutes a day of walking. If you're unable to commit to this, you're likely not yet ready to make truly measurable changes, so you might choose to end your read here. For those who want to see calorie math that genuinely adds up over time, stick around.

Let's look at the math using the logic of the study and MET score data (a topic for another article):

Let’s now look at the impact of different daily durations committed to wearing a vest while walking and running.

And for the final math equation: what does this equate to in terms of fat loss?

I don't know, it certainly seems like it burns more calories!

To answer the question from the perspective of someone who does this for a living, while staying true to my own values: if something is incredibly easy to add to an activity that should already be the foundation of your weight loss journey (like walking a lot), is there really much argument against it? We're talking about a 7-10% multiplier, which is essentially "free" if you're already doing the activity.

In most scenarios involving someone who already has a movement base rooted in NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis) and walking, a weight vest is a home run.

WHOOP There it is

WHOOP there is is.

Let me start by saying I wanted to hate the WHOOP ecosystem. This is very relevant to my review because everything I say here is going to be my opinion, but I would assume most of you would take what I say grain of salt. This is fair especially if what I say is a bit biased...I'm most definitely not biased towards liking WHOOP, if anything I am biased toward really thinking WHOOP is dumb and stupid.

Let me explain.

One of the first questions I needed answered when I was doing my initial research was "does this thing count steps." I figured this is a company that wants to track activity, sleep, and recovery so I wanted to make sure I didn't need another device to track steps. What I found was the dumbest answer a company could possible give, in my opinion, coming from the perspective of health and weight loss.

"Why we don't count steps"

To summarize the WHOOP article it challenges the traditional practice of counting steps as a measure of physical activity, arguing it lacks nuance and fails to account for exercise intensity and other forms of movement. Instead, WHOOP advocates for measuring "strain," a metric derived from heart rate data that quantifies the cardiovascular load your body experiences throughout the day. Strain offers a more comprehensive understanding of physical exertion, adapts to your body's readiness, and can serve as a motivational tool, making it a superior alternative to step counting for assessing overall health and fitness.

This device may be a inroad to better health but from the perspective of a weight loss tool it is not. I don't even agree with this really in the slightest in terms of intensity because output is output, but I do understand the direction they are taking. At a base level they are saying steps don't offer nuance, which I agree with, but it is still arguably the best universal health and weight loss/maintenance tool. They fundamentally don't think walking is enough, which I don't agree, but I do agree intensity as a cumulative variable is not experienced enough. I also agree with the fact that people just aren't working hard enough in general, so pushing what they call "strain" isn't a bad thing. I just think there is a place for walking...but more on this in the review because walking and rucking does actually move the needle enough to drive the same end goal I look for in my practice so it ends up not being a non issue in my opinion.

TLDR; this article by WHOOP is stupid and makes them look like they have no idea what they are talking about, but they also aren't trying to market the area of long term general population health and weight loss/weight loss maintenance...which is fine.

So with a name like @walk.more.king on instagram we aren't off to a great start here, but I really wasn't interested in it as a step counter so it doesn't really matter. The idea of chasing steps isn't really something you need a tracker for, walk more...how much more? More than you are doing if you aren't hitting your goals. A number is great, but ultimately it isn't rocket science, but it is a nice feature that I do think is relevant for people that think they are getting enough movement but the reality are not.

THE GOOD

It works, it's simple, and it collects everything all the time.

My biggest concern was that generally heart rate straps across the chest are going to be the most accurate. It's not even close when compared to wrist measurements of really any smart activity tracker worn on the wrist. What this means is that if you are someone who wants to nerd into the data or are focused on recovery...you want data that is representative of your actual workouts, especially as you start pushing the higher intensities. Without that accurate data you can't really get the most out of all the data.

Now obviously you don't need a heart rate strap to know when a workout is hard. That being said, if you are banking on other metrics to give you an idea of the whole picture it isn't entirely helpful if the main thing you need recovery from isn't being tracked properly. This was my main problem, especially with jiu-jitsu. There was almost no good way to track the data given that it is a contact sport. The heart rate strap was a pain to wear and track on a seperate app during a workout, and any wrist tracker is out of the question because it presents a place for your training partners to get snagged, cut, or catch a finger (not good....). So my main form of pushing intensity minutes in a week was going untracked.

Now this video is what ultimately made me go with the WHOOP.

TLDW (watch): A series of heart rate comparisons with a heart rate chest strap and WHOOP connected via armband. It shows about a 95% accuracy rating compared to the chest strap even at higher zone 4/5 intensities. The wrist wearing band is about at 60% which is essentially useless.

Now on it's own the bicep band is pretty unobtrusive and can easily be hidden below the shirt sleeve, but the double benefit is it does not get in the way nearly as much during jiu-jitsu training. Even more unreal is that they sell garments that allow you to disconnect from the tradition band (wrist or arm) and insert it for wearable tracking on boxers, shirts, pants, etc. I didn't really care about any of those because they are super expensive and I wasn't really interested in diving in the accuracy of the tracking on all parts of the body, but one piece that did stand out to me was the arm sleeve reader.

The arm sleeve is essentially a shooter sleeve for your bicep that takes the same arm reading as the band but has a much more secure feeling, especially when doing contact sports. Its perfect for wrestling and grappling and solves my biggest gap in collecting the data. It does move a bit, especially if someone grabs my arm and yanks it, but as a whole the concept is that I can wear this during rolling, it is covered and not going to injure my partners, it doesn't feel nearly as restrictive or painful when partners put pressure on it (like the chest strap), and it's easy to move back into position when it does move.

It also works like a charm.

So with the arm band and the arm sleeve it was a game changer for me because you can get chest strap-ish heart rate ratings, while being able to wear it all the time.

THE SECOND GOOD.

You can wear it all the time and it collects all the data.

Now this seems like a obvious point, but anyone who is used to smart watches or a chest strap is that the battery life is the bottleneck in collecting all the data. Generally you'll take these devices off to charge for an extended period of time making the night the easiest time to do so. You end up missing a large portion of data, especially the sleep and hrv data, which can be argued isn't the most amazing data sets on any devices...but if you stay within one ecosystem having ALL the data for the WHOLE day would be the most ideal situation.

Also, anyone who has collected legit HRV data generally you do this recording first thing upon waking up, put your chest strap on, open your app, and stay still for 1-2 minutes while it gets your most consistent HRV score. I don't know about you, I'm generally woken up by a 2 year old telling me to "wake up!" and before children I could barely get out of bed on a good day, littlelone go through the arduous process of getting an ideal HRV metric.

The WHOOP solves all of this by having a charger that clips on while you wear it. Genius. You literally don't have to take it off; which means you collect all the data all the time. Both device and charger are waterproof (at least by most standards) which is great. For someone like me who doesn't need another set of things to get in the way of collecting ALL the data, I just have to put a charger on every few days...literally that's it.

It just works...all the time and it's always collecting. Probably the sales pitch that got me the most to be honest.

THE THIRD GOOD.

I like the app.

*I should note that this thing is completely useless without the companion app. There is no display, no buttons, nothing...it's literally a brick. So you can stop reading this if those things are important.

The set it and forget it nature of the WHOOP is my favorite part of it, it collects all the data, it works, but how do the data get processed and displayed? This is a very important piece and the companion app does a bang up job. Basically every metric that it tracks can be evaluated on a daily, weekly, monthly chart, including neat monthly and yearly pdfs that do a review with insights for you to go through on your own time. There is a daily display of heart rate when you turn your phone sideways, which is awesome to do a quick check. It also calculates and gives you your daily strain and recovery score which are essentially the biggest pieces of information in terms of using it for your own training purposes.

As mentioned before strain is the WHOOP metric for how much work you have done in a day and it involves evaluating cardiovascular load. It does an amazing job of collecting cardiovascular load (strain) when pair with the bicep strap or sleeve for all my activities. I can literally track during the day, during a ruck, during grappling. Which as mentioned before was non existent because I couldn't actually collect the data due to wrist strap or chest strap falling off or not being in a good location for safety of training partners (catching on their skin or face, etc.). That being said, it doesn't give you the whole picture of how much work you've truly done, especially when you factor in muscular load i.e; lifting weights may not always present a cardiovascular load but it does produce systemic and local fatigue.

If you have a brain you can use your recovery score to make connections.

Now this segways into the...

THE FIRST BAD

If you aren't good at understanding your own circumstances, training, nutrition, sleep, this is going to be a problem because although it does a great job of collecting the data it isn't the best at making connections between very variable circumstances. For example, if I go on a long ruck with a lighter weight for over and hour (easily done when I'm working on my walking treadmill with a weighted vest) my strain is almost not even effected, but I can be completely fatigued...but my cardiovascular load wasn't significant. This in turn will have an effect on my overall ability to recover generally affected the recovery score. So high strain doesn't always equal low recovery and low strain doesn't always equal high recovery...which doesn't make logical sense if we think about these metrics in a very simple manner.

Now, I personally don't care.

I want it to track all the data in it's own ecosystem so I can operate the same as I usually do and create my own decisions based on the data, not necessarily it's recommendations. It won't connect that rucking makes my recovery go down a bit because it doesn't read it as a strain inducing activity...but it is. So how I personally use it is that I use the strain metric to register how much cardiovascular load an activity has, which it does a great job of, but I can't use that metric to measure fatigue accurately. The way you have to measure fatigue is generally to take your activities in a day, how you feel in the morning, and the recovery score. Which ends up being an after the fact observation that can be used for future situations that are similar, but strain alone won't tell you much.

At the same time, since it has all the data it isn't entirely that hard to figure these things out...BUT if you aren't that consistent with behaviours and activities you will have to simply trust the recovery score as your MAIN metric and just play with ti.

SECOND BAD

It doesn't track steps.

I already talked about this, but to me an overall picture of cardiovascular load should also come with the ability to understand what things DON'T affect cardiovascular load. This is more an opinion but right now you are left to your own devices to connect Non-excercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) with whether or not it provided any load and it doesn't make the connection for you, which in an app that has every insight (metric for journaling things you did in a day) under the sun to connect to recovery score...it doesn't use steps? The idea that walking could be a cardiovascular load enough to push strain would be an indicator that you need work, on the the opposite end the more more movement you get not pushing any form of measurable cardiovascular load would be an indicator, along side it's other metrics, that you are in fact progressing.

Also, if I go back to the journaling aspect in regards to making what they call insights, which are essentially self reported objective behaviors that the algorithm gives their "insight" whether it is helping or hurting your recovery, how is step count NOT an insight? Makes no sense, especially with the current research all point towards my favourite bias: more movement is more better for everything.

PRICING

This one's a bit neutral for me because although I don't like the monthly cost, it doesn't actually create a big price differential unless you somehow never replace old devices. In that case the monthly charge if you buy annually is about $27 CAN is pretty steep. That being said, most devices are $400 CAN plus so I mean you are looking about a year to a year and half on the subscription before you start losing money. I'm not actually for or against this pricing model, but non of the other products really provide the same benefits...so they aren't really an option. It is literally the only reliable option for what I want to track.

At the same time, if you aren't into combat sports, martial arts, and don't care about the hands off experience...get an aura ring or a fancy watch. Especially if you are into tracking steps as a a la carte experience.

FINAL VERDICT

This thing is awesome.

Steps aside, the selling feature for me is the ability to wear this thing 24/7 and be almost completely hands off if I choose and get my data. The addition of easy to easy bands and garments to collect data in different spots gives some customization for those who want better placement or just the ability to track things where the wrist measurement fails. Charging while wearing the unit is also something that every company should figure out because taking the unit on and off every night (the most logical time to charge) completely makes it almost useless outside of specific activity tracking.

They give everyone a promo code to give everyone a free month who you refer, which honestly isn't horrible. You get a free month and if you don't like it...you send it back...BUT let's be honest...no one is sending this thing back if you went through all the effort to research it. It's a sales ploy to capitalize on our inherent hate for using the ancient mailing logistic system...so just take the free month and give me my kick back for writing this article. Which I will use to buy more months because I don't collect fancy colored wrist bands because I don't wear it on my wrist because it's not that accurate.

Get a free WHOOP 4.0 and one month free when you join with my link: https://join.whoop.com/5A6427

should you cold plunge?

The hype around cold plunging is reaching its peak. I'll admit I've joined in, but perhaps not for the same reasons many of you have. On a scale from skeptical to naive, I sit in the middle. Most of my performance and recovery beliefs stem from personal experiences during my athletic days. While I still view myself as an athlete, the scholarship days are behind me. At the same time, I'll more than likely try most things to see what the hype is about because I would consider myself someone who doesn't like to leave any stone unturned...but I will turn those stones right back over if they are useless.

Cold plunging was not a stone I need to turn...it was already a part of my life.

Cold plunging, though a trendy term now, isn't new or groundbreaking. I'd even call it old and nostalgic. I have been using some form of cold therapy, mainly ice baths, since I was was a college athlete 15 years ago. It's what you did. In fact, much of our recovery involved icing our injuries, taking ice baths, or divisively tossing ice at unsuspecting teammates in the locker room. Currently ice bros are selling cheques that can't really be cashed by talking about all the dopamine they are going to get with their cold plunge routine...the real ones were just looking to get through two-a-days without feeling like we got hit by a train.

Ice was life.

Now as one does when their number one plan to play professional football doesn't work out and they retire, we do what worked. The problem is we are left without the paid resources of football team...one of those resources being ice. If you know anything about ice you know it is not only an incredible pain in the ass to make in quantities need for an ice bath, it is also insanely inconvenience and time consuming getting a bath tub to the temperature needed to shrink your balls out of existence and burn your skin. Luckily I had no good reason to need an ice bath because I starting lifting weights competitively and that just really wasn't that hard...so I never really thought of it until everyone and their mom started to talk about the NEW recovery method that could change your life. Little did I know, all the normies who couldn't make it out of high school athletics had now discovered the holy grail to self improvement and recovery...let me get in on this cold plunging...wait?

It's essentially just an ice bath.

Also to my surprise all those years I was partaking in freezing my balls off so I could avoid of a bit of DOMS (delayed onset muscle soreness) and drag my ass onto the field. I was unknowingly reaping other benefits. I remain skeptical, but let's delve into it.

WHY DO THE BROS LOVE THE COLD PLUNGES?

1.MOOD ENHANCEMENT

Without getting to in the weeds with this stuff the basics is that exposure to cold appears to trigger a cascade of biochemical reactions in the brain that facilitate positive emotions and reduce negative ones. This could potentially be used as a natural and cost-effective treatment for mood disorders such as depression, ADHD, or just general overall feelings of well-being.

A recent study by Tipton, et al. 2023 found that short-term immersion in cold water facilitated positive affect and reduced negative affect. Participants reported feeling more active, alert, attentive, proud, and inspired after a 5-minute cold-water immersion. They also reported reductions in distress and nervousness.

The study used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine the neural mechanisms underlying these effects. The increase in positive affect was associated with a unique component of interacting networks in the brain, including the medial prefrontal node of the default mode network, a posterior parietal node of the frontoparietal network, and anterior cingulate and rostral prefrontal parts of the salience network and visual lateral network. This component emerged as a result of a focal effect confined to a few connections.

Changes in negative affect were associated with a distributed component of interacting networks at a reduced threshold. These affective changes after cold-water immersion occurred independently, supporting the bivalence model of affective processing. Interactions between large-scale networks linked to positive affect indicated the integrative effects of cold-water immersion on brain functioning.

This sort of matches what all the bro science is alluding to which...cold exposure of any kind makes you feel unstoppable, driven, and well...like you jumped in a cold tub of water.

Not surprising, but also take that with a grain of salt.

2.BROWN FAT. BURN ALL THE FAT.

One of the big selling features of investing your time in the cold is this idea that being exposed to the cold activates brown adipose tissue (BAT) in the body. The short version is that BAT is much easier to burn off in our body and the reaction of this is increased body temperature to keep vital organs at the right temperature as well as regulate our core temperature in the present of cold. As we get more and more acclimated to cold exposure, the idea is that our body starts to produce more brown fat as an adaptation and thus increase our energy expenditure.

This idea of expending more energy is where a lot of the folk lore around cold exposure gets in magnetism...go in the cold, burn more calories, get more shredded.

When we are babies we have quite a bit more BAT because as an organism we haven't developed the ability to warm up as efficiently and rely a lot of the times of an external source. BAT tends to come in handy when we are much younger, but lose it mostly through adolescence as muscle mass, contraction, and movement start to produce much more internal heat regulations. aka it's not needed, so it naturally starts to decrease.

So cold plunging is thought to reverse this.

Unfortunately if you look through the evidence, there isn't really any meaningful increases in quantities of BAT, and given that adults don't actually have that much BAT it's safe to assume it's not moving the needle in a large measurable way.

3.IMMUNE FUNCTION.

I'm not going to lie, this one is very intriguing to me. I am the father of a 2 year old who goes to daycare regularly and I absolutely hate being sick. For anyone who is in a similar position you will understand that you have ZERO chance of being able to dodge whatever sickness is going around because kids are kids...they lick the ground, they touch each others faces after eating and not cleaning, they try to eat everything, and just having a child is the worst idea for anyone who is afraid of getting sick; don't have kids if this is you.

Why am I intrigued? Let me share a story that the 'bro science' side of me believes. I used to be a teacher...teachers are around people, a lot of people. Generally germs go to schools to produce, multiply, and infect EVERYONE. That being said, I was under the belief that being exposed day in and day out that I had developed a super immunity. I took one sick day in 4 years, I was invincible.

I wanted this super power back and cold plunging promises to develop this.

The long story short is that exposing yourself to the cold helps stimulate the immune response to the cold, thus increasing not only exposure to these responses, but building them to be vigilant through what I deem "strength" training of their ability to mobilize. It's a great thought.

Couldn't find any meaningful research other than Wim Hoff's word for it. So until then, the power of belief is a powerful thing. Much like my super power teaching...the placebo effect goes a long way. Embrace it, but now you know.

4.DOMS TRAINING RECOVERY

The most comprehensive literature review on Cold-Water Immersion (CWI) comes from Moore, E., Fuller, J.T., Buckley, J.D., et al. They conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on CWI's impact on passive and perceived recovery post-exercise. Now this is a fancy way of saying they looked at over 50 studies involving CWI specifically in regards to recovery metrics associated with high intensity exercise (dynamic movement they called it) and eccentric exercise (lifting).

What they found wasn't overall surprising for anyone who has used ice or cold in any sort of post athletic venture; it helped. It did study a bunch of outcomes but the ones that I think are the most helpful for the direction of this blog are delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS) and perceived recovery. DOMS is simply how sore are you post exercise, especially the next day...which sucks for anyone who has pushed themselves or experienced the "being hit by a freight train" feeling. Perceived recovery is well...how recovered do you feel, which is important because a lot of the time what we perceive may be the most important piece, particularly if you don't care about science ;)

Now breaking down the specifics of what it actually helped is where scientific jargon can get convoluted but some insights on where we can start to point us in the right direction to start monitoring our own subjective experience.

CWI had a large effect on reducing DOMS after high intensity exercise.

CWI had a moderate (less) effect following eccentric exercise.

CWI increased feelings of perceived recovery ONLY after high intensity exercise.

WHY I COLD PLUNGE

I'll be candid here. Broadly speaking, I see two potential paths:

Sell you on all the hype associated with cold plunging to get some traction.

Tell you my truth.

Option 1 would be logical if I had affiliations or received free products from cold plunge companies, but that's not the case. I see no problem pushing a product a bit more enthusiastically than I would if I wasn't affiliated, especially if I actively use or like it. that being said, I am not popular enough to garner the attention of big cold and either way I wouldn't promote claims that aren't true.

I would rather just lay it out that way I see and let people that want to try it out or are thinking about it make a decision based on what I believe is a pretty balanced opinIon on it. What I mean by that is I'm not going to shill cold plunges, but I'm also not going to hate on them because I'm an insecure little bitch who wants to chase clout...

This is simple here's what I think and here's what I did. Enter at your own risk.

HERE'S WHAT I THINK

When it comes to incorporating new things into my life, my thought process is straightforward: Is the payoff worth the time and effort for me? When it comes to recovery I'm looking for more or less low time commitment, high pay off. For me this ensures that I will be able to keep it in my routine and actually be able to do it long term. A common pattern I've observed is that many activities start with high enthusiasm, only to fizzle out later. I prefer not to engage in such fleeting pursuits. If I do something I want to do it all the way so I can really decide for myself if this thing is worth it or not.

Unfortunately (or fortunately..I don't know), when we are talking about cold adaptations, a lot of the benefits come from continued use over time and the ability to continue and apply the stimulus (being in cold water) without much of a lay off. This means that skipping weeks and months at a time more or less detrains the adaptations fairly fast. So to me this isn't something you do once or twice a month if you want to be able to achieve anything close to what some of these studies and claims are selling. This is a big deal, because unless you have the ability to use this thing multiple times per week, it's not going to do much for you. So in order for me to even find out if this thing is worth it I had to more or less figure out at way to do this thing multiple times per week.

In my area, achieving this is nearly impossible without owning a cold plunge, as no businesses offer them. Just perfect...

I then considered, if my only viable options are to buy or build one (more on that in the next article), whether the scientific evidence, personal anecdotes, insights from Huberman/Attia podcasts, and Reddit discussions are convincing enough for me to 'take the plunge.

My answer hinges on its purpose. Am I using it for recovery from BJJ (Jiu-Jitsu) to enhance my training frequency? In this scenario the answer is an easy yes. Considering DOMS and overall feeling like your body is on the brink of breaking is literally the worst part about BJJ and the biggest detractor from the little voice in my head saying "don't train today," I think cold plunging is my best answer outside of sleep and nutrition. It's a low time commitment, it works both from a scientific research stand point and it I have a fairly extensive personal background with it during my college career, and you literally don't have to do anything but sit in cold water. That's it.

If you reasoning for doing it is hack your mood and for productivity?

I mean it works but I don't know if the videos I see on instagram claiming is the equivalent of doing cocaine really pan out. There is definitely mood enhancement, feelings of being energized, happier, accomplished, are all more or less present; sounds like drinking coffee without the coffee, but not cocaine. There are enough people claiming it changed there life and this can't go unnoticed and for whatever reason whether it's the dopamine rush or the flood of epinephrine positive associations are overwhelming present. I just can't guarantee you will be one of those people and if you are, how much is that worth to you?

If your reasoning is for the increase in brown fat and the ability to burn more fat?

Not bullshit but negligible in terms of its ability to increase energy expenditure in any real meaningful way. That being said, this adaptation will make it easier to withstand cold much better which has its benefits if you do anything in the cold. Generally it isn't sold as this though, like I mentioned before, the brown fat adaptation isn't a "fat loss" adaptation that creates more expenditure that will target and destroy regular fat...it literally just helps you stay warmer and has almost a zero net effect on overall energy expenditure. Want to train to stay warmer? Well ice plunging checks if you consistently use it every week and convince the body to start adapting via brown fat up-regulation.

Is there any other reason?

Another perspective I've considered is that consistently using a cold tub can serve as a habit builder, training oneself to tackle challenging tasks. I do nutrition coaching as a profession and a lot of the times the barriers are to success rarely lie in the understanding of the simple science. The ability to say no or make the "hard" decision when we live in a world that in constantly evolving to make life easier, highly palatably easy to access and afford, and make money sitting on our asses, gets harder and harder.

In terms of a skill builder the way I tend to try and rationalize if something is effective is that does how much effort does it require and is the skill required to participate low enough for a person to have a shot at being successful? In both of these scenarios the answer is fairly positive because it requires almost no physical skills or effort...you literally have to be able to get into a tub of water and sit in it. It gets a little murky when we factor in mental skill requirements of the getting into the actual tub and the cognitive load of anticipation of the inevitable freezing you balls or metaphorical balls off. This is both hard to quantify and even harder when you factor in that you either have to build your own cold tub to make is easily accessible or travel somewhere that has one. Those two factors alone are barriers that I think realistically makes this hard enough most people won't be using a cold plunge long term unless they have ease of access.

This is more of a theory I've yet to delve deeply into. But when it comes to skill-building, there are few passive activities (like simply sitting in cold water) that offer tangible benefits. In my opinion, ice baths do cultivate this resilience. At the same time if you need to build this skill you probably aren't someone who is going to go through the process of building your own cold plunge, investing $5000+ on purchasing one, or making a daily commute just to use one. You are probably someone who needs advancements in teleportation to beam you to a cold plunge or beam a cold plunge to you; in both cases I'd say this is a bust.

SO WHAT DID I DO?

I built one myself.

As with many things I undertake, it didn't take much to convince me that I needed a cold plunge in my house right away. I'll try anything and after doing a bit of research on youtube and reddit I figured out a way to do it at a fraction of the cost.

The first step I took was researching what the best cold plunge companies are selling to create a home set up. I realized really quickly that there was no cold plunge on the market that was cheap. We are talking easily over $3000 for anything that doesn't rely solely on ice too achieve cold water temperatures (more on that in my next blog about how I built my set up).

Spending $5000+ on something that could cost $2000 or less seems unreasonable to me.

Much like most things I tend to do myself, if I think I can do something on my own or better for a fraction of the cost, I'm going to do it. It might not always be as nice, but in this situation a cold plunge or ice bath is literally cold water. This should not cost 5000$, especially when temperatures recommended fall anywhere between 39-55 degrees F and my cold Canadian water comes out at 50-55 without any outside chilling sources.

Stay tuned for more...

SIT MORE?

Throughout my athletic career, my lack of mobility has been a constant source of amusement for my peers and myself. Despite my high-level athletic performance, I've always struggled with basic tasks like sitting cross-legged or comfortably settling into low positions. This might not seem surprising given my background in football and powerlifting, sports that transformed my body into something resembling a refrigerator more than a flexible athlete.

But the joke stopped being funny when I realized that my stiffness was preventing me from fully engaging in everyday life. I was strong, but I couldn't easily get down on the floor to play with my child.

My new athletic pursuit, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, further highlighted my limitations. My stiffness was leaving potential results and enriching experiences on the table. So, I started asking myself: How can I begin to solve this problem in the most effective way possible, with the least amount of effort? After all, like everyone else, I'm "busy."

In our Western society, we've engineered our environments for maximum comfort. We sit on plush sofas, work from ergonomic office chairs, and sleep on mattresses tailored to our individual preferences. We've essentially eliminated the need to engage our bodies in the ways our ancestors did. But while these comforts have their benefits, they also come with a cost.

Our bodies are designed for movement and variety. When we spend most of our time sitting in chairs, we're not using our muscles as nature intended. This lack of movement and muscular engagement can lead to a host of issues, from decreased mobility and flexibility, as I experienced, to chronic pain and even increased risk of diseases like diabetes and heart disease.

Moreover, our comfort-based practices often promote poor posture. Slouching on a couch or hunching over a desk can lead to imbalances in the body, which over time can result in pain and injury. And while we may not feel the effects immediately, the cumulative impact can be significant.

In my case, my athletic training had made me strong, but it hadn't prepared me for the demands of everyday life or the flexibility required for Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. I was experiencing the drawbacks of a lifestyle and training regimen that prioritized strength and performance over mobility and flexibility. And I knew something had to change.

Sanctuary

There hasn't been a lot of "buzz" around sitting positions. But for me, the inspiration came from an unexpected source: the Netflix show "Sanctuary." Despite what its name might suggest, "Sanctuary" isn't a meditation guide or a deep dive into Buddhism. Instead, it's a riveting series centered around sumo wrestling—one of the best I've seen in recent years.

Now, you might be thinking: what does sumo wrestling have to do with sitting? On the surface, not much. But when you delve into the cultural context—Japanese culture, to be precise—the connection becomes clear. As I watched the series, I was struck by how these massive athletes, who compete in a physically demanding sport, adopted sitting positions that I would typically associate with a chair or couch. Whether cross-legged or kneeling (butt to heels), they were consistently low to the ground. They slept on thin mattresses on the floor and even used the bathroom in a deep squat. Their days were devoid of the lounging postures we're accustomed to in Western societies. And the most surprising part? These sumo wrestlers, who you'd expect to be stiff from the demands of their sport, displayed flexibility that outmatched anyone I know.

This observation was a revelation. It underscored a truth I've encountered time and again in my research: our environment shapes us more than we realize. Our bodies are incredibly adaptable, responding to the demands we place on them. But those demands are often dictated by our environment—an environment we can control, yet often allow to be shaped by societal norms.

When we become aware of the qualities we want to cultivate, the solutions start to appear in our everyday activities. Conversely, the same can be said for negative adaptations.

So yes, a show about sumo wrestling transformed my perspective on sitting positions.

The Problem with Comfort: A Modern Dilemma

Lately, I've been considering a thought-provoking question: "How have our modern comforts contributed to our current problems?" This isn't to demonize all comforts—far from it. Instead, it's a lens I use to scrutinize my current habits and assess how they align with my goals.

Just as the sumo wrestlers in "Sanctuary" were shaped by their environment, so too are we shaped by ours. But unlike the sumo wrestlers, our environment is often filled with modern comforts that encourage passivity and limit our range of movement.

Like many of you, I relish the opportunity to unwind with Netflix on a cozy couch or in bed, letting the world pass me by. It's a pleasure I'm not willing to give up. But what if the way I enjoy Netflix could be influencing my body's mobility, or worse, exacerbating my stiffness?

The truth is, we could probably afford to sit better. With minimal adjustments and without the need for extra materials, we could easily incorporate better sitting habits into our daily routines. And the good news? We can make these changes faster than we might think.

Now, comparing one sitting position to another might seem like a strange argument. After all, sitting is sitting, right? But bear with me. In our modern world, where earning a living often involves long hours in a chair, where furniture is designed for passive relaxation, and where entertainment is increasingly sedentary, we might just be getting too comfortable.

Before I delve into my proposed solutions, let's examine two key aspects of my argument.

The Power of Active Resting Postures

Our modern lifestyle often leads us to spend a significant amount of time in sedentary positions that may not be optimal for our health. But what if there were a different way to rest—one that could actually benefit our health and well-being? This is where the concept of active resting postures comes into play.

What Are Active Resting Postures?

Unlike sitting in a chair, which allows our muscles to relax and can lead to poor posture, active resting postures such as squatting and kneeling require us to engage our muscles even while at rest. This can lead to increased muscle activity, improved posture, and potentially better overall health.

The Power of Active Resting Postures: A Lesson from the Hadza People

In the vast savannah-woodlands of Tanzania, the Hadza people lead a lifestyle reminiscent of our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Despite being sedentary for about the same amount of time as people in Western societies—around 10 hours a day—the Hadza exhibit few of the health problems typically associated with a sedentary lifestyle. The secret to their health may lie in the way they rest.

Unlike the chair-sitting habits prevalent in modern societies, the Hadza engage in what researchers call "active resting postures," such as squatting or kneeling. These postures, while seemingly restful, require a higher level of muscle activity than sitting in a chair. This constant engagement of muscles, even during periods of rest, could be a significant factor in their resistance to chronic diseases associated with long periods of sitting.

In the study "Sitting, squatting, and the evolutionary biology of human inactivity," researchers propose the Inactivity Mismatch Hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that human physiology is adapted to more consistently active muscles, derived from both physical activity and from nonambulatory postures with higher levels of muscle contraction. This adaptation is a stark contrast to the muscular inactivity associated with chair sitting in industrialized societies.

The Hadza active resting postures may provide additional protection against the negative health effects of sedentary behaviors. Their non ambulatory postures elicit higher levels of muscle activity, which may trigger health-related benefits throughout the day. This finding challenges the conventional understanding of rest and inactivity and suggests that the way we rest, rather than the amount of time spent resting, could have significant health implications.

The Hadza people's lifestyle offers a window into our evolutionary past and presents a compelling case for rethinking our modern sedentary habits. While squatting or kneeling for extended periods may not be feasible for everyone, the study suggests that replacing chair sitting with more sustained active rest postures may represent a behavioral paradigm that should be explored in future experimental work.

The Benefits of Active Resting Postures

Research suggests that active resting postures can have a number of health benefits. For one, they can lead to increased muscle activity which can help to counteract the negative effects of sitting. They can also improve posture, as they require us to maintain a more upright position than sitting in a chair. In a roundabout way it is also a way to push the main concept of high flux or atleast higher flux for a very common position, sitting, or atleast the way we are currently sitting with low muscle tension and active requirement.

Moreover, active resting postures could potentially help to protect against the health problems associated with a sedentary lifestyle. While more research is needed to fully understand these benefits, the case of the Hadza suggests that changing the way we rest could have a significant impact on our health or atleast a possible clue into where certain health outcomes may comfrom considering the overall movement isn't significantly different from day to day. Obviously vastly different reasons with the hadza being low energy so the cost of extra movement isn't worth the risk vs. our current society sits because most jobs and activities are done sitting...on chairs.

How Can We Begin to Implement This into Our Day-to-Day Lives?

Before we dive in, I want to clarify that this isn't a here-is-all-solutions guide to reclaiming your inherent mobility and adopting active resting postures. That would require a book. That being said the task may seem daunting, especially given our current macro environment and culture and I want to provide some things I think can help. I believe that a few high-leverage changes can significantly impact your personal microenvironment at home or work. These changes can allow you to enjoy tangible results while still navigating the realities of our modern lifestyle.

Answering the question of implementation is straightforward, but the application might be more challenging than we anticipate. The solutions vary based on:

Whether we accept the social and cultural norms of our environment and seek workarounds—or what many in the fitness world would call "hacks."

Whether we are willing to challenge some fundamental habits we may have been following our whole lives. These changes would be harder to implement but potentially more effective if we can figure them out.

In most scenarios, people want "hacks," which is understandable. However, this desire also plays into a common theme where most things go wrong: the reluctance to step out of our comfort zones. But I also recognize that it takes time and small, consistent efforts to bring about significant changes.

So, what are these "hacks"? For ease of understanding, I'll list them out:

Squat or Kneel While Playing with Kids: If you have children, use playtime as an opportunity to practice active resting postures. This not only benefits you but also sets a positive example for your kids. It's worth noting that kids often naturally adopt these positions because the world is still a bit too big for them. This representation allows them to hopefully maintain these habits, so they don't lose them and have to rebuild them later—which is the point of this blog.

Kneel While Reading or Working: If you're reading a book or working on your laptop, try kneeling instead of sitting on a chair. You can use a cushion or yoga mat for added comfort.

Squat or Sit on the Floor During TV Commercials: Use the commercial breaks as an opportunity to practice active resting postures. Start with a few seconds and gradually increase the duration as your comfort and flexibility improve.

But what about the more significant changes that aren't "hacks"?

The idea here is that hacks are good and can add up over time, but the real changes are going to be ones that are built into your daily life you don't have to think about. As humans we tend to take the path of least resistance and if you offer a way out, we generally are going to take it unless you are aware and override that. That being said, overriding these things is actually a pretty stressful task and realistically noone wants to say no to everything over and over again...so what is the solution?

Don't give yourself the option. Change your environment completely to fit the desired outcome. Live.

Now note this could be taken to any extreme you want and this blog is not design to list all of the degrees in which you can change your environment but I'm only going to list one that I think can have the biggest impact:

Low sitting desk: In my case I chose to bring the floor up to my desk with a makeshift platform, but the idea is that we work 6-10 hours a day and a large number of us do this sitting...in chairs. Simple remove the chair. If you are like me you don't want to by a fancy set up like THIS , you simply bring the floor up to whatever desk you have. In my case I used a workout bench and a box squat platform...but the concept is simple. I have since switch to a DIY platform where I can sit how ever I want (seiza chair in displayed here). The thing is you just need to ditch the chair so you don't have the option.

This doesn't mean you should avoid sitting altogether—that's nearly impossible. However, if we replace or at least partially replace our highest volume of current sitting postures with an active position, we've completely flipped the game around. Your highest volume of inactivity could become your highest volume of a posture that restores your mobility, increases muscle tension, and possibly unlocks the ability to do other things (like getting up and off the ground with your grandchildren).

Let me emphasize that concept: ditch the chair.

That's it.

One final point:

There's been a lot of talk recently about the need to work out to prevent muscle loss as we age. This is a great sentiment. However, what do we typically lose as we age? Generally, it's the ability to move around and get up and off the floor. Most age-related injuries stem from some sort of fall. So, what's the benefit of a low active resting posture? It requires you to get down on the ground and get into position.

The real kicker, though, is that it requires you to get up.

As the 40-year-old virgin asks, "If you don't use it, do you lose it?" In this case, the answer is yes...yes, you do. So why lose it in the first place and have to react by needing to work out when you can just change your environment and never lose it?"

WHY HIGH FLUX?

Why high flux could be the answer we have always been looking for.

As an aspiring fitness enthusiast, a high flux diet can be the difference between you crushing PRs in the gym, building a monster engine, and increasing overall jacktitude or floundering about in a low energy state.

Learn why eating more and doing more is the holy grail of long term performance and body composition.

It doesn’t matter who you are, if you are trying to lose fat and maintain it long term and the only tool in your toolbox is to lower calories…you are screwed. Straight up. Many of the simple stories that we constantly see usually start and end with that ONE thing:

You just need to eat less. You just need to workout more. You just need to move more.

Is it really that simple? Yes and no. Although many of these interventions work, initially, it isn’t very helpful to consider them THE answer. This especially starts to become a thin argument when we look at people as individuals, with different genetics, different environments, and different lives. So, in the real world are these simple stories useful? I’d argue that they are dangerous, especially when people blindly follow expert advice.

SOLUTION? HIGH ENERGY FLUX

Although I am against simple stories, if we combine them, we start to develop a better answer that gives us some more options. Again, we are avoiding this ONE thing mentality and I have found this concept of higher energy flux much more useful as a coach and as an individual.

What is energy flux?

It is the movement of energy through a system.

Calories in = Calories out

The things we eat = The things we do

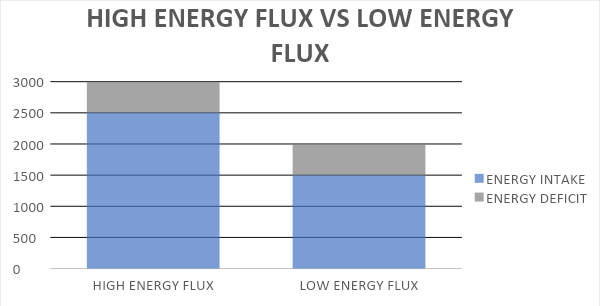

When we look at higher energy flux versus lower energy flux, we are simply looking at eating more and doing more versus eating less and doing less. The SAME person can be in a DIFFERENT energy flux while being in an energy deficit, balance, or surplus. The main difference is the calories one has to take in to be in balance, this will determine your starting point for either a deficit or a surplus. CRAZY.

THE MATH

The same person can be eating 3000 calories or 2000 calories and theoretically be in the same deficit depending on which energy flux they are currently in.

We actually have two recent studies that looked at this exact equation and we can start to see the potential benefits.

The first one is a study by Humme et al. 2016 [1] which looked at 239 subjects (154 adolescents and 75 women) did baseline testing with a 3 year (adolescence) and 2 year (women). The major measurement outside of RMR and BF% was their TEI and TEE, or simply energy balance. They tested this using a 2 week doubly labeled water test to see what their energy balance before and after.

The results are pretty shocking because the simple story is that the people who eat less should theoretically lose weight over time…but this isn’t what happened. When they compared subjects in a higher energy flux (eating more and doing more) to lower energy flux (eating less and doing less), the higher energy flux actually PREDICTED long term weight loss. The crazy thing is that the subjects in lower energy flux actually GAINED weight in the long term.

The second study is by Paris et al. 2016 [2] was a study with 6 obese adults (BMI of 30 and not dieted for 12 months) where they looked at high energy flux versus low energy flux. After a weight reduced period (7% body weight) and a stabilization period of 3 weeks, they tested both energy balances for 4 days.

Although this study didn’t look at long term weight loss, it did present findings related to hunger that are interesting, but ultimately logical. During the low flux period participants were subjectively hungrier for the 4 day period by a huge margin. This is HUGE for anyone looking to push the human system long term in either a fat loss period or weight maintenance period. Hunger can derail the best of us, especially in our current environment where hyperpalatable foods are in abundance.

Lastly, and this is completely observational, we live in a world of excess and unlimited food cues. From an evolution perspective we are designed to eat food because as our hunter gatherer ancestors evolved, they realized food was scarce, it was costly energy expenditure wise, and when it was in abundance, they ate ALL of it in preparation for periods of low food availability. We DON’T have that problem anymore. What we are left with is this system that is designed to eat food when we see food…and we see food at almost every turn in modern day society; imagine being hungry and if that is a situation that is helpful to our fat loss or weight maintenance goals.

TO SUMMARIZE:

Being in a higher energy flux is predictive of long-term fat loss. Higher energy flux is one of our best weapons to fight against a hostile environment that is very easy to overindulge. Hunger signaling is much lower when someone is in higher energy flux.

Perfect…higher energy flux is a great tool to use, but what does that look like in the real world? How do we push this thing?

EAT MORE.

The one thing we can always fall back on in the fat loss world is that lower calories is the gift that does NOT keep giving. After weight loss occurs energy expenditure starts to become reduced unconsciously (Non resting energy expenditure) because our system is trying to conserve calories. This is adaptive thermogenesis.

All this means is that the lower we go calorie wise, yes, we lose weight initially, but that process slows down over time because our bodies are amazing systems and become increasingly efficient. This process happens over a period of time and can have major implications for our ability to lose or maintain fat loss long term.

So, eat more.

Harris et al. 2006 [3] did an amazing overfeeding study that looked at individuals who were fed 1000 calories above their weight maintenance calories for 7 days straight. Although I wouldn’t suggest this long term, there was actually an increase in BMR (Basal metabolic rate)/metabolism acutely and a slow increase over time. This paints the picture that it isn’t as simple as eating less and eating more can actually turn up the system and allow us to burn more energy.

The one thing to note is that when compared to other overfeeding studies this response to change in BMR was variable. This is exactly what I see observationally as well. Sometimes when dealing with nutrition clients, we get to the point where we are trying to maintain fat loss and an increase in calories actually causes them to lose weight. On the other end, adding calories sometimes means that they just maintain or slightly gain on much more calories.

DO MORE. MOVE MORE.

If you're reading this, I'm assuming you're already incorporating some form of physical activity into your routine. While the specifics of your workout regimen are best left to your personal trainers or coaches, my goal here is to provide you with a fresh perspective that could help you achieve your fat loss goals more effectively.

One of the most compelling examples of the "do more, move more" philosophy is the Amish community. Known for their simple, traditional lifestyle, the Amish are largely engaged in physically demanding occupations like farming, woodworking, and construction. A study by Bassett et al. 2004 [4] revealed some astonishing facts about this community. Despite consuming a diet rich in calories, fat, and refined sugar, the Amish community exhibited remarkably low obesity rates. The secret? A high level of physical activity.

The Amish men averaged 20,000 steps per day, while the women averaged 15,000. This level of physical activity, coupled with a high-calorie intake, is a perfect example of high energy flux - eat more, do more, move more.

This is high energy flux.

EAT MORE, DO MORE, MOVE MORE.

Now, these are only recommendations and there are a lot of details that are going to be contextually dependent, but that is where this information becomes a guideline. If long-term fat loss or weight maintenance is the goal, we need to take a different approach if we want it to be sustainable. Give the body what it needs, find the modality that you want to use to push physical activity (for me its lifting weights), and move more throughout the day. This isn’t game-breaking advice but combining these tactically is often overlooked as an intervention.

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE

If we are looking to move people on from the perpetual purgatory of dieting, we need to start looking at higher flux diets as an intervention. How do we start this process? Take all the simple stories and combine them.

Increase calories. Start at an additional 250-500 per day (likely towards that higher-end if you’re reading this) and make small increments as your metabolism adjusts.

Increase your daily step count. It’s one thing to crush workouts, but your training actually accounts for a small amount of your overall activity throughout the day. If you want to truly become a metabolic furnace, you need to move more. Period. Start with an additional 1,000 steps per day from where you are currently at and get to the point where you’re getting in at least 10k throughout the day.

Increase your physical activity using whichever metric you use to track progress. This is the good stuff – set some performance metrics and get after it. If you improve your output, you’re improving your ability to move energy through your system.

Remember when it comes to coaching people through nutrition or doing your own nutrition, this is about leverage points. Which areas do you struggle with? It is incredibly easy to do the stuff we are good at but if you have an opportunity to attack some of the areas we tend to overlook, we may start to develop better answers.

The purpose of this article is to highlight that things are not always simple and being simple can lead us down some less than ideal situations. Use the concepts and tools you have available and start to create a plan that doesn’t leave you preaching “Just Eat Less.”

References:

[1] Hume, D. J., Yokum, S., & Stice, E. (2016). Low energy intake plus low energy expenditure (low energy flux), not energy surfeit, predicts future body fat gain. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 103(6), 1389–1396. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.127753

[2] Paris, H. L., Foright, R. M., Werth, K. A., Larson, L. C., Beals, J. W., Cox-York, K., … Melby, C. L. (2016). Increasing energy flux to decrease the biological drive toward weight regain after weight loss – A proof-of-concept pilot study. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, 11, e12–e20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnesp.2015.11.005

[3] Harris, A. M., Jensen, M. D., & Levine, J. A. (2006). Weekly changes in basal metabolic rate with eight weeks of overfeeding. Obesity, 14(4), 690–695. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2006.78

[4] Bassett, D. R., Schneider, P. L., & Huntington, G. E. (2004). Physical Activity in an Old Order Amish Community. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 36(1), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000106184.71258.32